Melanoma is the fifth most common type of cancer. It is a malignant tumour that generally appears as a black, irregular mark on the skin. In contrast to non-melanoma skin cancers, melanoma may appear before the age of fifty, may be more aggressive and can spread to form metastases (secondary cancers) in other tissues.

Origins and causes

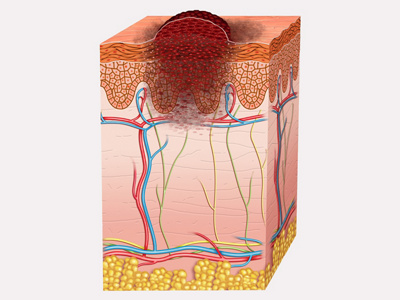

Melanoma skin cancer, also called (malignant) melanoma, originates in the pigment cells (melanocytes) that are present in the basal cell layer of the epidermis. It develops slowly over the course of several months or years and eventually becomes visible on the surface of the skin. In rarer cases it may also occur in the mucous membranes, eyes or brain, or arise from existing moles.

Like non-melanoma skin cancers, a malignant melanoma forms as a consequence of overly strong or intense UV radiation. Too prolonged or unprotected periods in the sun damage the skin, as does strong radiation from artificial sources such as sunbeds. This changes the genetic material in the melanocytes in such a way that a malignant tumour develops. Melanoma is particularly dangerous because it can result in metastases, which are secondary growths that affect other organs and the surrounding tissue.

People with pale skin are more at risk of developing malignant melanoma. Also at greater risk are those with many or large moles, especially if they have a mole that is a mix of colours (dysplastic). Moles can degenerate over time and become cancerous. A family history of melanoma also increases the risk.

Symptoms

Melanoma usually appears as an irregular, black mark on the skin. These can vary considerably in appearance, from small and flat to large and raised. However, in contrast to non-melanoma skin cancers, melanoma can form not only in sun-exposed areas, but on any part of the body. It is therefore important to look carefully.

In addition to the dark colouration of the skin, malignant melanoma can also itch and bleed in later stages, and may be associated with poor wound-healing. Pain is unusual. If a mole turns malignant, the first warning signs are spontaneous bleeding, a red border forming around the edges, or changes in shape or colour.

Symptoms like these should be taken seriously and be examined promptly by a dermatologist. If the tumour is found early, then it can be treated before it spreads to form secondary cancers or grows more deeply into the skin. This increases the chances of successful treatment.

Diagnosis

Melanoma is divided into different types:

- Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM): As it initially only spreads on the surface, with early diagnosis there is a good chance of a cure.

- Nodular melanoma (NM): This type of tumour grows to be more raised, feels lumpy and tends to bleed. It is often only discovered at an advanced stage.

- Lentigo-maligna melanoma (LMM): This develops slowly from a pre-cancerous condition called a lentigo maligna. This type of melanoma often appears on the face, and resembles a lentil in shape.

- Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM): This type looks like a bruise. It generally appears on the palms of the hands, on the soles of the feet and under the nails.

The first step is to determine what type of pigmented skin lesion it is. To do this, the specialist examines it with the aid of a dermatoscope or epiluminescence microscope. This makes it easier to make out the structure and to distinguish it from a mole. The affected area can then be diagnosed using the ABCD(E) criteria:

- A = Asymmetry (asymmetrical halves, i.e. non-matching)

- B = Border irregularity (uneven edges)

- C = Colour variation (a mix of colours, or changes in colour)

- D = Diameter (over five millimetres)

A further parameter may be used to give additional information following long-term observation:

- E = Elevation (measurable growth of the pigmented area)

If one or more of these criteria are met, then it is likely to be malignant melanoma. After this initial assessment, a special ultrasound device is used to measure the thickness of the tumour and find out how deeply it has penetrated the skin and whether it has started to spread. A tissue sample is taken during a biopsy, which is examined and analysed in a laboratory. If a malignant melanoma is diagnosed, the attending doctor will draw up an individual treatment plan

Treatment of melanoma skin cancer

The aim of treatment is always to remove the cancer entirely. To this end a variety of different treatments may be used, sometimes in combination.

Surgical treatment

The first step is to surgically remove the melanoma along with a little of the surrounding tissue as a safety margin, to guard against a return of the disease. After the excision, the tumour is sent to the laboratory to be examined and checked for signs of radial growth. If these are present and extend to the edge of the area that has been cut out, then more tissue needs to be removed from that area. Smaller and easily accessible tumours are removed by a dermatologist. Larger interventions are carried out by specialist surgeons. Plastic surgery will also be involved if any skin grafts are required.

After removal of the tumour, it is measured and analysed in the laboratory. If it is thicker than one millimetre and without any visible signs of spreading, then a biopsy of the sentinel lymph nodes can tell us whether cancer cells have spread from the melanoma into other organs. ‘Sentinel lymph nodes’ is the name given to the nearest lymph nodes to the original tumour. The reasoning is that the cancer cells would have had to pass through these lymph nodes in order to spread further, and would therefore be detectable in these tissues. The result is key to deciding on the course of further treatment.

Adjuvant therapy

Whenever possible, melanoma skin cancer is treated surgically. Depending on its size, position, spread and the health of the patient, subsequent supportive (adjuvant) therapy may also be useful. This can prevent the formation of new tumours and eliminate any metastases that have not yet been discovered.

Supportive measures include:

- Medication therapy

- Radiotherapy

Medication therapy

If the tumour has spread to other organs, there are various groups of medication that can destroy the cancer cells in the body.

- Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy involves prompting the body to attack the cancer cells itself. The diseased cells are either ‘labelled’ in such a way that the immune system can recognise them and start working against them, or the drugs actively trigger an immune response against the cancer cells.

- Targeted drugs: Certain drugs work in the cells themselves. With targeted treatment, they can attack the signalling structures of the cancer cells and thus inhibit their growth.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy uses what are known as cytostatic drugs to hinder the growth and division of cancer cells in the body. Tumours then shrink, or disintegrate completely.

Radiotherapy

If the melanoma has formed metastases in the brain, lymph nodes, bones or other areas that are sensitive or hard to access, then the tumour can be treated with radiotherapy that is gentle on the surrounding tissue.

Your specialist will tell you about the chances of success and risks of all the different types of treatment in an individual consultation

Prevention

Prevention of malignant melanoma requires careful and consistent sun protection. This means:

- You should always apply a sun cream that protects you from both UVA and UVB radiation, even on cloudy days.

- If you are going to be spending long periods outside, wear clothes that cover most of your skin.

- Try not to spend time outside during the hours when the sun is strongest (between 11 am and 3 pm).

- Avoid sunbathing and, whenever possible, try to stay in the shade.

The UV damage that later leads to melanoma often originates in childhood or adolescence. This means that moles should always be kept under close observation and any dark changes in the skin should be checked by a specialist doctor. If it is found early, melanoma can be successfully treated and spreading can be prevented.