Listen to your gut feeling

Measuring up to eight meters in length, the intestine is our longest organ. It is no surprise that the intestine is also called the second brain. It contains over 200 million nerve cells and up to 100 billion bacteria. No wonder that there is a close link between healthy gut flora and human health.

This topic page contains fascinating facts about the intestine, tells you how to keep it healthy, and outlines the most common discomforts and conditions.

Busting the myths around digestion

The intestine

Did you know...?

Vegetarians usually have a larger stool volume than meat eaters.

One person’s gut flora contains about 100 billion living organisms such as bacteria, viruses and fungi.

The human intestine can be up to 8 meters long thus making it our longest organ.

Over the average lifetime, the intestine processes about 30 tonnes of food and 50,000 litres of fluid.

The gut flora consists of more than 500 different types of bacteria.

It takes about 3 days for a meal to pass through the entire digestive tract.

The intestine is the centre of the human immune system. It contains about 70% of our immune cells.

The small intestine renews its cells round the clock: on average, it replaces its mucous membrane every 2 days.

Gut bacteria weighs about 2 kg in total.

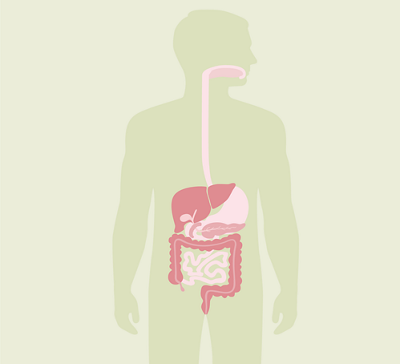

The human digestive system

The oesophagus

The oesophagus is about 25 centimetres long and about 2 centimetres in diameter. It is responsible for transporting food and fluid from the mouth to the stomach and is divided into three parts: the cervical, thoracic and abdominal sections. The thoracic section is the longest part of the oesophagus; it is about 16 centimetres long. The oesophagus is stretchy and is lined with mucous membrane on the inside. This mucus helps the food slip down into the stomach.

The stomach

The stomach is located in the central and left upper abdomen. Its deepest point is about where the navel is. The size and shape of the stomach depends on how full it is, the position of the body and the person’s age. The stomach of an adult can hold about 2.5 litres. It stores food until it is expelled into the small intestine in small portions mixed with gastric acid and digestive enzymes to be further digested. The production of gastric acid in the stomach also neutralises pathogens.

The stomach is divided into different areas: cardia, fundus, body and pylorus; the pylorus is divided into the antrum and the pyloric canal. The latter of these areas leads to the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. Pushing movements (peristalsis) force the chyme, the semi- fluid mass of partly digested food, towards the duodenum. The small intestine can usually only contain pieces of chyme that are smaller than 2 millimetres in size.

The small intestine

The small intestine is divided into three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum. It is relatively small in diameter compared to the large intestine, but is somewhat longer. The small intestine of an adult is about 3–4 metres long.

Food is further broken down in the small intestine until only the basic building blocks remain. Water intake also plays an important role: 80% of the water in the chyme is absorbed in the small intestine.

The small intestine is wound into intestinal loops. These small intestinal loops increase the surface area of the small intestine, which creates a larger contact area between the chyme and the intestinal wall, allowing for more absorption. The chyme also moves more slowly through the intestinal loops than it would through a straight pipe, which increases the time when it is in contact with the intestinal wall and facilitates the absorption of nutrients. The blood and lymphatic vessels then transport the nutrients to where they are needed.

Intestinal villi

The small intestine contains about 4 million villi, which are 1 to 1.5 mm long and 0.5 mm thick. The intestinal villi are made up of thousands of microvilli. As in the stomach, the contractions (peristalsis) of the small intestine ensure the mixing and movement of food.

The duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine. It is about as long as twelve fingers, and C-shaped. This is where the majority of nutrients are absorbed. The inner, round side of the C rests on the head of the pancreas. The duodenum does the necessary preparatory work so that the chyme can be digested in the later sections of the small and large intestine. In the duodenum, enzymes produced in the pancreas and gall bladder are added to the chyme. Without these enzymes, the other parts of the small intestine would not be able to digest the chyme any further.

The jejunum

The jejunum is the middle part of the small intestine and about 2 metres long. As in the duodenum, the jejunum further breaks down food components and absorbs nutrients. In addition, the jejunum produces mucus which completely covers the interior of the small intestine and thus protects the mucous membrane from self-digestion by the acidity of the stomach.

The ileum

The last section of the small intestine is the ileum. It is about 3 metres long and cannot be clearly separated from the jejunum. Anatomically, the ileum is similar in structure to the other sections of the small intestine. However, the wall in the ileum is not quite as thick and has fewer villi than the other parts of the small intestine. This is because most of the usable food components have already been absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum. In the last part of the ileum, Vitamin B12 is absorbed from the food.

The large intestine (colon)

The colon is about one metre long and is wrapped around the small intestine. Approximately 0.5–1.5 litres of intestinal content pass from the small intestine into the large intestine every day. The large intestine can process the residue from the small intestine for up to three days. In the large intestine, the remaining nutrients (water and salts) are removed from the chyme. This thickens the chyme. In addition, mucus is added to the chyme to make excretion smoother. Many different bacteria, viruses and protozoa live in the large intestine. All of these microorganisms are called gut flora. Healthy gut flora is important for regular digestion. The bacteria extract minerals and vitamins from the final undigested residue, strengthening our body's defences in the process.

The ascending colon

The ascending part of the large intestine begins above the entrance to the small intestine and runs to the flexure (bend) in the intestine under the liver.

The transverse colon

The transverse colon runs horizontally through the upper abdomen to the intestinal flexure under the spleen.

The descending colon

The descending part of the colon runs from the left upper abdomen down into the lower abdomen.

The sigmoid colon

In the left lower abdomen, the intestine has a slight S-shaped curve. At the end of this curve, the large intestine passes into the rectum.

The caecum

The caecum is located on the right side of the lower abdomen. Attached to it is the appendix, which can become inflamed. The caecum contains cells of the lymphatic system that fight off diseases, thus having a significant influence on the immune system. In addition, the caecum is considered a refuge for various intestinal bacteria. For example, if (vital) bacteria is destroyed during an infection, it can move from the caecum to other parts of the intestine.

The rectum

The rectum stores the stool so that it does not have to be constantly excreted in small quantities. The rectum is about 16 centimetres long and forms the connection to the outside via the anus. When the rectum is full, we feel the urge to go to the toilet.

Common conditions

Bowel cancer

Bowel cancer is the third most common type of cancer in Switzerland. The risk of this type of cancer increases with age. Bowel cancer develops from intestinal polyps in 97 % of all cases. Symptoms include altered stool habits, rectal urgency without a bowel movement and blood in the stool.

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Two of the most common chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The latter can occur throughout the entire digestive tract (from the mouth to the anus), whereas ulcerative colitis only affects the large intestine and the rectum. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and fever can occur in both diseases.

Gastrointestinal infection

Gastrointestinal infection, also known as gastroenteritis, manifests as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. It is an acute inflammation of the digestive tract. Bacteria and viruses often trigger gastrointestinal infections.

Irritable bowel syndrome

One of the most common diseases of the gastrointestinal tract is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Symptoms of IBS are long-lasting and recurring abdominal pain, a feeling of fullness, diarrhoea and/or constipation. Around 10–15 % of the Swiss population suffers from irritable bowel syndrome. It’s a lengthy problem and the symptoms can come and go, lasting for days, weeks or months at a time.

Diverticula

Intestinal diverticula are protrusions in the intestinal mucous membranes. They can appear in the small or large intestine. If the bulges filled with faeces become inflamed, this is known as diverticulitis, which must be treated with a bland diet, antibiotics or surgery, depending on its severity.

Appendicitis

The disease is called appendicitis because the appendix, rather than the caecum, becomes inflamed. Appendicitis usually manifests as abdominal pain, which moves to the right lower abdomen within a short period of time and can become very severe.

Colorectal polyps

Colorectal polyps are benign growths in the intestinal mucous membranes that protrude into the cavity of the intestine. Colorectal polyps can vary greatly in size and shape. As they grow, they can degenerate, i.e., develop into malignant tumours (bowel cancer).

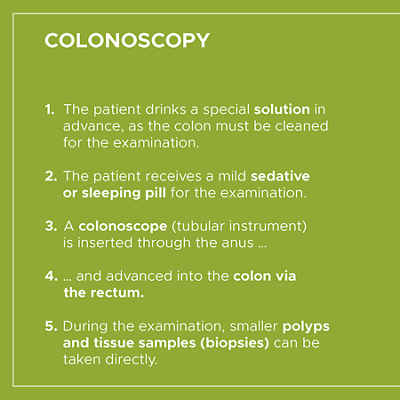

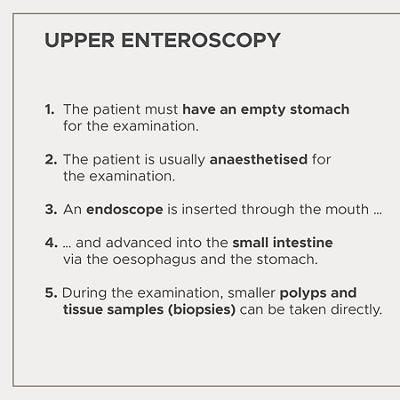

Bowel examinations

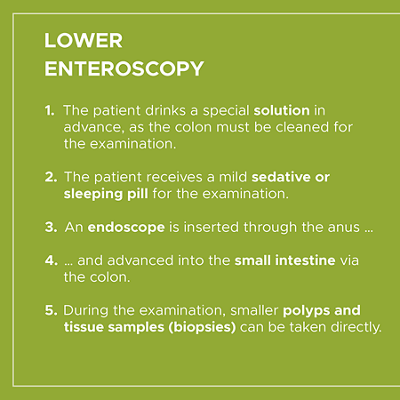

During a colonoscopy the doctor can examine the inside of the intestine with the help of a camera and check for pathological changes. Colonoscopy is an examination of the large intestine and rectum, whereas enteroscopy is an examination of the small intestine. Since the small intestine of a human being is about 3-4 meters long, a complete enteroscopy is only possible if it is performed from below and above.

How the examinations are performed exactly:

Where to find us

Centre de gastroentérologie et endoscopie digestive

1205 Genève

Dr Bertolini +41 22 347 46 91

David.Bertolini@hirslanden.ch

Dr Morard +41 22 346 19 93

Isabelle.Morard@hirslanden.ch

Dr Nguyen +41 22 347 55 66

Thai.NguyenTang@hirslanden.ch

Tumorzentrum Hirslanden Zürich

Bitte wenden Sie sich für die Anforderung der Arztberichte direkt an den behandelnden Arzt

Unsere Onkologie (Sprechstunden, Termine) erreichen Sie unter:

+41 44 387 37 80 oder info@kho.ch

Für Fragen/Anmeldungen zu den Indikationsboards (für Nutzer) erreichen Sie uns unter: +41 44 387 96 55 oder indikationsboards@hirslanden.ch

Für administrative Fragen zu den Zertifizierungen erreichen Sie uns unter:

+41 44 387 96 62